Charles D. Bernholz, Love Memorial Library, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588 [*]

Brian L. Pytlik Zillig, Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, Love Memorial Library, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE 68588 [**]

Cokie G. Anderson, Electronic Publishing Center, Library Annex, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078

Abstract

Text analysis is a rapidly growing endeavor within the digital world. The development of effective tools will accelerate progress in this area and, simultaneously, unveil aspects of selected materials that may never have been previously studied.

This article introduces TokenX, a text visualization and analysis tool that will expedite such examinations. The use that may be derived from its deployment is demonstrated through the creation and assessment of the two lexicon corpora of American Indian treaties made with the federal government (N = 368), and of those documents formed during the earlier British occupation (N = 7). Token frequency tables for these families of instruments are included.

In pursuance of the order of the late Congress, treaties between the United States and several nations of Indians have been negotiated and signed. These treaties, with sundry papers respecting them, I now lay before you, for your consideration and advice, by the hands of General Knox, under whose official superintendence the business was transacted; and who will be ready to communicate to you any information on such points as may appear to require it.

Go. Washington.

New York, May 25th, 1789."

[1]

The 1621 text of the Conference and agreement between Plymouth Colony and Massasoit, Wampanoag sachem (2003) reveals one of the earliest attempts to negotiate with American Indians. In this anonymous report, it is recounted that Massasoit (c. 1590-c. 1660) "saluted us in English, and bad us well-come, for he had learned some broken English amongst the English men that came to fish at Monchiggon" (p. 23). [2] The settlers apparently took this as a fortunate event, "questioned him of many things," and after the Plymouth Governor and Massasoit exchanged toasts with "some strong water" and food, "treated of Peace." The resulting six part transaction advocated nonaggression ("That neyther he nor any of his should injure or doe hurt to any of our people"); alliance ("If any did unjustly warre against him, we would ayde him; If any did warre against us, he should ayde us"); and security ("That when their men came to us, they should leave their Bowes and Arrowes behind them, as wee should doe our Peeces when we came to them") (p. 26).

About a dozen years later, Roger Williams concluded land transfers with the Narragansett (Williams describes original Narragansett deeds, 2003, p. 46) after "severall treaties" and a purchase, from the same two participating chief sachems, that "established and confirmed the boundes of these landes from the river and Fields of Pawtuckqut and the great hill of Neotacoconitt on the northwest, and the towne of Mashapague on the west."

These negotiations and conveyances were examples of early diplomacy that led eventually, over the next 250 years, to 375 recognized treaties between the British and federal governments and the American Indians, and to "[t]he purchase of more than two million square miles of land from the Indian tribes [that] represents what is probably the largest real estate transaction in the history of the world" (Cohen, 1947, p. 42). O'Brien's volume on Indian lands in Natick, Massachusetts, between 1650 and 1790 — Dispossession by Degrees (1997) — was far from being misnamed. The strategies used by the Natick Indians to sustain their culture were prototypic examples of adaptation made by other tribes during any period of later American Indian policy. Frequently, the enforced rules for such changes over these years were found in the texts of the treaties, recognized or not.

English Language Diplomacy

Peter Tiersma, in his Legal Language (1999, p. 23), described the rise of English as the language of diplomacy when, in 1650, Parliament legislated that all case reports and legal publications would appear in this language alone. Legal standards migrated to North America along with the settlers and the judicial formats here followed closely those of Britain. Tiersma also remarked upon the extensive vocabulary in the legal profession in a chapter entitled The Legal Lexicon, concluding quite directly that "the legal lexicon differs in many ways from ordinary speech and writing," and that "[j]argon and technical terminology are problematic because they actually facilitate in-group communication while greatly reducing comprehension by the public" (p. 114). It would follow that comprehension, regardless of the clientele, must risk further deterioration in a multilingual setting.

For a modern exemplar of successfully navigating these difficulties one may turn to the Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Finland and the Government of the People's Republic of China Relating to Civil Air Transport (Agreement relating to civil air transport, 1978). This brief fifteen-article document discusses the "establishment and operation of scheduled air services between their respective territories" (p. 68). These eleven words of text are part of an English translation of this instrument; the document text was published in the languages of the cosigners, Finnish and Chinese, with versions in English and French attached.

The potentially difficult path to convergence on a final version of this Agreement was smoothed by reliance upon English during their discussions. The final statement in the English version of the document reads (p. 73; emphasis added): "Done at Peking on this second day of October, 1975, in duplicate in the Finnish, Chinese and English languages, the three texts being equally authentic." Such an endeavor would have been more precarious if only the two nations' languages were employed, or — even more so — if only one of these was engaged, but the current prevalence of English in all international matters no doubt helped expedite the transaction. There might be an even more pronounced reason for the use of English here: it is "the lingua franca of the world of aviation" (Aust, 2000, p. 202).

In a slightly different universe, Michael Silverstein's article for the Annual Review of Anthropology used oenology, viticulture, and oenophilia in a model for the development of a prototypic lexicon appropriate to the discussion of these specific ventures. He proposed that "[a]t each of the phases of the sociocultural life of wine, interested people come together in various kinds of events that centrally involve discourse, using language in genre-specific interactional events. As in many similar cases, then, language in use thus becomes a mediating tertium a quo between humans and their fashioned agricultural and aesthetic commodity, wine" (2006, p. 484). [3] This ability to derive the true "meaning of 'meaning'" for such words and phrases allows anthropologists and linguists to compose a "lexicography [that is] actually useful to — in fact, [is] a central enterprise of — the ethnographic task of understanding cultures" (p. 487). The development of such specialized units of a language – here, to describe aspects of the production, assessment, and economics of wine within Silverstein's special "sociocultural" environment — offers a view of the people who participate in these particular activities, and so the "lexicography as such becomes, in part, an ethnographic undertaking. It blurs the boundary, if ever one wanted to invoke one, between what was intended by the 'dictionary' of a language and by the 'encyclopedia' of knowledge of a culture" (p. 493). In his concluding paragraphs, Silverstein remarked that "[a]t every culturally recognizable node in the trajectory from production to consumption, then, there will be special lexical registers that conceptually define the object of discourse, frequently with a view back or forward to other nodes in the chain of sites. Physical and political geography, as well as fermentation history and methods, are frequently invoked on bottle labels destined to be read and understood by connoisseurs" (p. 493; emphasis added). The very development of such registers, therefore, allows communication to progress.

Application to the Tribes

The lexicon of the "physical and political geography" of wine is no more or no less important than that in the development of an appropriate lexicon for diplomacy. By applying Silverstein's perspective, the identification of the functional lexicon used in legal instruments such as treaties would serve to create a better understanding of the processes that these negotiations entailed. Indeed, Haycox's history of Alaska (2002, pp. 20–21; emphasis added) described a similar parallel topography for the events that took place in the colonization of that area: "Political geography differs from physical geography; it deals with the power that individuals and groups exert over others and over the land. Its origins can only be understood in historical context. In terms of the physical geography, most political geography is artificial; it dissects natural boundaries willy-nilly, without regard to natural physiographic features, integral ecosystems, or perhaps most significant, cultural units."

However, there are added language impediments to successful diplomacy. From another perspective, Silverstein (1996; p. 117) examined among Indian tribes the dynamics of linguistic contact that "develop as a function of the sometimes abrupt, sometimes protracted, shifts in the sociopolitical relations of indigenous peoples one with another and each with the heterophone newcomers." Jones (1988, p. 185) had acknowledged earlier that negotiations with the tribes were "not conducted by trained diplomats but by anybody and everybody: by orators, civil leaders, village and provincial councils, missionaries, speculators, traditionalists, dissidents, those with authority and those without." This point was reinforced in the essays on these languages in the Americas between 1492 and 1800, contained in Gray and Fiering (2000), that began with a very succinct perception of the issue (pp. vii-viii): "The burden of overcoming language barriers was a problem faced by all peoples of the New World in the early modern era: African slaves and native peoples in the lower Mississippi Valley; Jesuit missionaries and Huron-speaking peoples in New France; Spanish conquistadors and the Aztec rulers. All of these groups confronted America's complex linguistic environment, and all of them had to devise ways of transcending that environment — a problem that sometimes arose with life or death implications." As a measurement of this convolution, Driver (1969) alluded to upwards of 2,000 Indian languages in North America at the arrival of the Europeans. Only a tenth of these — 221 — were known well enough to have been classified (pp. 43–45) and that number had dropped to "approximately 209" by 1995 (Goddard, 1996, p. 3). [4]

Coupled, then, with the increasing demands over time for land cessions that likely accompanied almost any discussion (see Kvasnicka, 1988), it must have been a chaotic and frightening time for the indigenous peoples of North America as they scrambled to learn the language of Silverstein's "heterophone newcomers" to protect their own interests under each newly arrived agenda that replicated in one manner or another the schema Haycox portrayed for the conditions in Alaska. [5]

However, the tribes had substantial experience of negotiating with others. This can be seen in the interactions in 1607 at Jamestown (Stith, 1865); the development of wampum as a form of communications (Jacobs, 1949); Lafitau's history of the characteristics of Indian diplomacy in eastern North America (1977, pp. 173–186); their treaty discussions with the Spanish (Kinnaird, Blanche, and Blanche, 1979); and the 17th century dialogues with the colonists of New York (Trelease, 1997; Feister, 1973). It is also reflected in the evolution of the Iroquois Confederacy (Aquila, 1983; Fenton, 1998), the creation of a new Covenant Chain, between Sir William Johnson and the Mohawk (Mullin, 1993) and the enduring images of this union (Shannon, 1996). [6] In particular, the scope displayed by the document compilations of Vaughan (1979-) and Deloria and DeMallie (1999) substantiates these experiences, while the dispensing of peace medals (Prucha, 1994b) at treaty conferences, begun during George Washington's administration, was a clear statement by the federal government that these events were perceived as more than just attempts to communicate with "savages," [7] and that appropriate, diplomatic protocol was in order.

Adaptations and Responses of the Tribes

Bragdon (2002, p. 121) spoke of the "complex relationship between vernacular literacy, the processes of colonialism, and the ways in which cultures are said to transform and reinvent themselves" in an evolving political environment. She also noted an interesting land-conveying document from 1706, written by Massachusett-speaking residents of Martha's Vineyard. [8] Goddard and Bragdon (1988, p. 61) had provided a translation of this agreement, which in part stated, "I Thomas Dilla convey land and I let Nathaneill Cuper have it." [9] It was proposed that this land transfer was an exhibition of "the continuing importance of oral argument, the presence of numerous witnesses, the archiving of written records, and the participation of several readers and writers in the creation" (p. 124) of such vernacular documents, thereby identifying skills that were particularly vital during negotiations with the colonists.

Little (1980) remarked upon the structure of about 250 such transactions from between 1659 and 1764 in the Nantucket Registry of Deeds. She found three general formats that were discernible by form and style — the so-called English deeds; the Indian deeds; and recorded oral land transfers. The first array numbered about 150 examples, and acknowledged purchases of Indian lands by British settlers. By about 1728, legal terminology began to appear as part of the process — "the phrase: 'give, grant, bargain, sell, alien, convey, and confirm'… had replaced the simple 'hath sold' of 1662" (p. 61). Roughly 90 Indian deeds were created between, and written by, tribal members over the years 1668 and 1702. These were produced with less legalese, and in many cases announced land gifts from tribal sachems. The few recorded oral land transfers contained the least text in English and were testimonies supporting conveyances only between tribal members up to about 1731; the British relied upon true deeds to support any of their transactions. Taken together, these legal documents were critical to the coordination of the lives of all the residents of Nantucket during this period.

In another tribal example, Silverstein remarked that Pidgin Delaware, a created contact language that was developed and used by both the tribe and the colonists, had a lexicon that was used in "functions such as trade, getting information about people, Christian ministry, and concluding formal (treaty) arrangements" (1996, p. 123; emphasis added). This focus must have been a useful development, since the Delaware were involved over time in more than twenty recognized treaties, beginning with the one that Charles J. Kappler used as the first document in his collation of recognized treaties with American Indians ( Treaty with the Delawares, 1778 ; Kappler, 1904b, pp. 3–5). [10] Jones (1988, pp. 190–194) illustrated how the Delaware were active participants in negotiations with the British during their colonial period by listing a series of tribal land cessions in Pennsylvania in the early 1680s. The degree of required interaction by these people alone would suggest that improved communications were mandatory. [11] Yet, unfortunately, the texts reveal nothing about the presence or the use of Pidgin Delaware on the paths to these final instruments. Further, the potential universality of English was for all intents nonexistent for these Delaware conversations, as well as when most of the remaining recognized American Indian treaties were negotiated.

The Evolving Creation of Indian Treaties

An examination of the history of the tribes is a multifaceted task. Extensive research into the myriad aspects of the lives of the original inhabitants of this country exposes the skills and efforts of these groups to sustain themselves within their own timeless worlds while simultaneously learning to interact effectively in a new, evolving one. The panorama of the Handbook of American Indians (Sturtevant, 1978-); the investigations of Father Francis Paul Prucha (1962 and 1994a) into the intricacies of federal Indian policy; the collation, by Charles J. Kappler (1904b), of the final texts of almost all recognized treaties with the tribes; and, for example, the thoughts of Dwight L. Smith [12] on the early people of Ohio are powerful examples of endeavors to reveal these societies.

Of special interest in this note on the lexicon of Indian treaties found in Kappler's collection is Smith's (1949) description of the migration of the Huron from Canada to Ohio. He specifically remarked that, in this process, the Huron lost their French name and became known to the British, through trading contact, by an approximation of their own name for themselves — the Wendat. Further, it was noted that they had had a difficult existence, reflected in part through their endless movement and by their involvement over the years in numerous treaties that conveyed land to the federal government. [13]

Smith wrote an account of Article 6 of one of these instruments, the Treaty with the Wyandot, etc., 1817 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 145–155). He disclosed (p. 309; emphasis added) that "[a] tract of land twelve miles square at Upper Sandusky and a second tract of a mile square on a cranberry swamp on Broken Sword Creek about ten miles from the northeast corner of the Upper Sandusky reserve were to be retained by the Wyandot." [14] An examination, however, of the Statutes at Large entry for the text of this treaty speaks of "a tract of one mile square, to be located where the chiefs direct, on a cramberry swamp, on Broken Sword creek, and to be held for the use of the tribe" (7 Stat. 160, 162; emphasis added).

The issue of a controlled lexicon for this specific Wyandot instrument is far broader than just a question of a botanical misspelling. In an example within a digitized suite of those nine treaties absent from Kappler's gathering, the search item on*d* located, in seven of these instruments, the terms Onandago, Onandagoes, Ondaghsighte, Oneida, Oneidas, Oneido, Onejda, Oneyde, Oneydes, Onnondage, Onnondages, Onnondagues, Onnaudague, Onondaga, Onondagas, Onondages, and Onondago (Bernholz, Pytlik Zillig, Weakly, and Bajaber, 2006). Absent Ondaghsighte, a sachem of the Oneida noted in ratified treaty number 1, The Great Treaty of 1722 Between the Five Nations, the Mahicans, and the Colonies of New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania (O'Callaghan, 1855a, pp. 657–681), these are names for two tribes in New York, the Oneida and the Onondaga. These variations appear in Hodge's earlier synonymy (1906, pp. 1021–1178) and, supplemented by even more options, in his individual entries for these two nations (pp. 126–127 and 129–133, respectively). Each of these tribes was an important participant among almost the entire assortment of these early British treaty negotiations, regardless of how their names were spelled. Readers of these documents then would have known clearly these various identities, perhaps just as well as readers today can fathom cramberry.

The presence of more than one name for individual tribes did not disappear after Independence and the quest for standardized spellings emerged. The seventh volume of the Statutes at Large holds treaties created up to the early 1840s and has titles for these documents that reflect the evolution of some tribal names. The terms Pottawatimies, Teetons, Yanctons, Poncarars, Chayennes, Mahas, Sissetong, Camanches, and Witchetaws are present in those Statutes, but Kappler's 1904 titles for the same documents declare instead the Potawatomi, Teton, Yankton, Ponca, Cheyenne, Omaha, Sisseton, Comanche, and Wichita tribes. Kappler was well aware of this spelling issue, and so, in Appendix I of his first volume, his explanation entitled " Revised Spelling of Names of Indian Tribes and Bands " declared that "[t]he spelling of the names of Indian tribes, bands, etc., contained in the following list has been agreed upon by the Bureau of American Ethnology and the Indian Bureau. So far as practicable the names are spelled phonetically, but it has been found advisable in several instances to retain, unchanged, names of foreign origin and those that have long been used as geographic terms" (1904a, p. 1021). This designation review had first appeared as an inventory of "Names of Indian Tribes and Bands" in the Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1900 (1900, p. 519). Nevertheless, even with this attempt to standardize formal names, Kappler's second volume was forced in some cases to accept other spellings, since the source for his collection of documents was ultimately based on the Statutes at Large versions of these instruments.

Frederick W. Hodge, in an epic work that formed the model for today's Handbook of North American Indians, observed (1906, p. v; emphasis added) that "in the literature relating to the American Indians, which is practically coextensive with the literature of the first three centuries of the New World, thousands of such names are recorded, the significance and application of which are to be understood only after much study." His "Synonymy" in that publication made this declaration quite evident and its use endures in the Handbook: a Wyandot synonymy accompanies Tooker's article (1978, pp. 404–406) with, inter alia, the terms Wondats, Owendaets, and Wayundatts from the mid-1700s.

These few tribal name examples make apparent that a unique list of words, as suggested by Silverstein (2006), should be contained in many of the treaties consummated between the British and the federal government and the American Indian Nations. Indeed, the "physical and political geography" attributes of this special "sociocultural" atmosphere required the development and evolution of such a focused treaty terminology. The language and the format of treaties with American Indian tribes thus changed over time, and this was dramatically so following Independence, but English persevered as the only official language of each of the transactions. [15] The New World lawyers, with their exposure to British legal traditions, felt that such documents should follow a more contractual model, instead of the narrative format style that was pronounced in the seven, earlier recognized treaties consummated by the British. This transition will be demonstrated below on the two complete lexicons — one American, one British — for all 375 acknowledged instruments.

The Examined Texts

Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 1904

Three hundred sixty-six of the 375 recognized American Indian treaties (Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722–1869, 1966) were assembled by Charles J. Kappler as part of a widely used compilation (Kappler, 1904b).16 This treaty collation has served as a fundamental resource for these transactions for over a century. Kappler, as Clerk for the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, compiled these relevant yet dispersed materials. Volume 2, in Serial Set volume 4254, contained 832 pages of these instruments (Kappler, 1903) and this assembly was republished the following year, as Senate Document 319 of 1,099 pages in Serial Set volume 4624, with format modifications that included lists of signatories and accompanying text (1904b). [17] The treaty volume was reproduced later in a separate edition (see Kappler, 1972 and 1973). [18]

The contents of volume two, in fact, consist of 388 documents. Fifteen of the 17 items in the Appendix (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 1027–1074) are not recognized treaties and were removed from this analysis. Only the so-called Agreement with the Five Nations of Indians, 1792 (p. 1027) and the Agreement with the Seneca, 1797 (pp. 1027–1028) in this group are acknowledged documents, classified by the Department of State as ratified treaty number 19 and 27, respectively. Seven items in the collection appear as stand-alone transactions, but they are supplemental materials that modified in some way, and are thus part of, an existing treaty and so were retained as part of this application.19

Overall, the published Kappler series begins with ratified treaty number 8, the Treaty with the Delawares, 1778 (pp. 3–5) and ends with ratified treaty number 374, the Treaty with the Nez Perces, 1868 (pp. 1024–1025). One questioned additional item, the Treaty of Fort Laramie with Sioux, etc., 1851 (pp. 594–596), has been recognized by the courts as a legal and binding transaction. [20] Except for this last item, it is generally thought that Kappler used the Statutes at Large as the source for his texts.

The individual texts used here were first converted from print to digital format by the Oklahoma State University Library (OSU), as part of a program to digitize all of Kappler's volumes. [21] For this lexicon analysis, the individual treaty files were copied from the OSU online website, and processed as described below.

Early Treaties with American Indian Nations

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln Libraries' Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (UNL) similarly digitized the nine remaining documents, consisting of seven treaties created by the British, and two American documents that were never published in the Statutes at Large. [22] The seven British transactions, and the sources used for digitization, were:

- Ratified treaty # 1: The Great Treaty of 1722 Between the Five Nations, the Mahicans, and the Colonies of New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania (O'Callaghan, 1855a, pp. 657–681);

- Ratified treaty # 2: Deed in Trust from Three of the Five Nations of Indians to the King, 1726 (O'Callaghan, 1855a, pp. 800–801);

- Ratified treaty # 3: A Treaty Held at the Town of Lancaster, By the Honourable the Lieutenant Governor of the Province, and the Honourable the Commissioners for the Province of Virginia and Maryland, with the Indians of the Six Nations in June, 1744 (Van Doren and Boyd, 1938, pp. 41–79);

- Ratified treaty # 4: Treaty of Logstown, 1752 (The Treaty of Logg's Town, 1752, 1906);

- Ratified treaty # 5: The Albany Congress, and Treaty of 1754 (O'Callaghan, 1855b, pp. 853–892);

- Ratified treaty # 6: At a Conference Held By The Honourable Brigadier General Moncton with the Western Nations of Indians, at the Camp before Pittsburgh, 12th Day of August 1760 (Hazard, 1852); and

- Ratified treaty # 7: Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary Line – Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 (O'Callaghan, 1857, pp. 111–137).

Two United States treaties were published only in the American State Papers and never appeared in the Statutes at Large:

- Ratified treaty # 28: Convention between the State of New York and the Oneida Indians, June 1, 1798 (American State Papers: Indian Affairs, 1832, p. 641) and

- Ratified treaty # 44: A Treaty Between the United States of America and the sachems, chiefs, and warriors, of the Wyandot, Ottawa, Chippewa, Munsee, and Delaware, Shawnee, and Pattawatamy nations, holden at fort Industry, on the Miami of the lake, on the 4th day of July, A.D. one thousand eight hundred and five (p. 696).

These last two documents were combined and analyzed along with the Kappler materials, since they were negotiated and signed by the United States. The primary final document set, then, consisted of the two suites of files. First, the so-called "American" collection was constructed of all the files necessary to describe the 366 treaties from OSU's digital Kappler Web pages, plus the electronic texts of the two treaties from the American State Papers. Second, the first seven recognized treaty items, taken from the UNL early treaty Web site, were placed into a "British" module.

Methods

TokenX, a web application developed by the second author with the support of UNL's Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (CDRH), was designed for analysis and visualization of Extensible Markup Language (XML) and Text Encoding Initiative-compatible (TEI) documents. Words in the text corpora are, for the purposes of analysis in TokenX, defined as strings of alphanumeric characters that are separated by whitespace or punctuation. Because apostrophes are sometimes contained within words, TokenX does not by default see these as word separators. Terms that begin with, contain, or end with an apostrophe are retained as a single token. Special characters, such as the 18th and 19th century ſ or long s, are represented in Unicode. [23] Words and non-words are individually marked up in XML to enable separate analytical processes. [24]

Treaty files from Kappler's collation were obtained from OSU in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) format and subsequently converted for text analysis. Similarly, the remaining nine instruments from UNL's Early Recognized Treaties with American Indian Nations web site were transformed.

There were four steps in the conversion. First, files were transferred into Extensible HyperText Markup Language (XHTML) by using HTML Tidy, an open source program and library for checking and generating HTML/XHTML. Second, the XHTML files were edited to eliminate any links used for navigation, email addresses, and boilerplate HTML content. Third, a series of files was created and then verified against the well-formedness constraints of the XML. Fourth, UNIX shell scripts and Extensible Stylesheet Language for Transformations (XSLT) stylesheets were employed to convert the XML files into TEI. [25]

The TEI files were divided into the two categories of American Indian treaties — the American and the British suites. Each category of documents was concatenated into a TEI corpus file. Original filename information for the OSU and UNL sources was retained; these data are potentially useful for linking text analysis results to the original document sites. Finally, the application processed each corpus and created an XML file that contained a word frequency data table. The two data tables were each converted into a Structured Query Language (SQL) relational database and these were queried using the scripting language PHP: Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP).

The Task

Separate analyses were executed for the British and the American documents groups, because the mode of treaty reporting was vastly different under the two regimes. In general, the British presented a description of the entire event, including the negotiations that accompanied the creation of these diplomatic transactions. Creating kinship between the two parties was an especially critical issue in these initial proceedings (see Bernholz, Pytlik Zillig, Weakly, and Bajaber, 2006), and so each treaty event was very much a social experience. This reporting style and sharp attention to forming enduring friendships carried over to some degree during the development of the far more contract-like American documents that were produced between Independence and the end of the War of 1812. After these latter hostilities terminated, however, the role of Indian tribes in the development of the United States was reduced and the need for the federal government to befriend or placate the tribes disappeared.

The American treaties (N = 368)

The corpus of these materials

There are 23,244 unique terms in these 368 documents, totaling over 640,000 words, but almost 14,000 or 60% are single occurrences, reflecting in part the names of the many participants at the signings, and of the various long schedule lists of land distributions to affected parties at these transactions. These terms were sorted alphabetically, and by word frequency.

Some Interesting Exemplars

The five American treaty words with the highest frequencies

The words the, of, and, to, and in range in descending frequency from 56,363 to 9,469 times. The three of the next four most frequent items are his, x, and mark, but these were used together throughout the treaties to indicate a mark in lieu of a signature, as in the confirmation Pierremaskkin, the fox who walks crooked, his x mark on the Treaty with the Foxes, 1815 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 121–122).

In relation to written British English, the five most frequent words in these treaty texts are ranked number 1 through 4 and 6 in the Lancaster-Oslo/Bergen (LOB) Corpus (Johansson and Hofland, 1989, p. 19), and are ordered first through third, sixth, and fifth in the more recent British National Corpus (Leech, Rayson, and Wilson, 2001, p. 181). In older, American English datasets, these terms had ordinal positions of first through fourth and sixth in the Brown Corpus results of Kucera and Francis (1967, p. 5), and spots 1, 3, 4, 8, and 6 in those of Francis and Kucera (1982, p. 465). In each case, the absence here of the word a disrupts the exact frequency order, as do the two other terms be and he in the 1982 example. The basic building blocks of English seem to have prevailed back then, even when the frequency counts of the elements in these texts are compared to more modern rate analyses.

Personal names

The American lexicon is saturated with names, as part of those listed in either schedules attached to treaties or as actual signatories to the documents. Kappler added signatories to the texts presented in his 1904 version of volume 2; the 1903 edition did not have these names. As a result, the names Cunningham ( Treaty with the Apache, 1852 ; Kappler, 1904b, pp. 598–600) and Sedgwick ( Treaty with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, 1861 ; pp. 807–811) are intermixed with Coo-wooh-war-e-scoon-hoon ( Treaty with the Arikara Tribe, 1825 ; pp. 237–239) and Tuskegatahu ( Treaty with the Cherokee, 1785 ; pp. 8–11). Æneas Mackay, "Lieutenant corps artillery," appears in the witness list for the Treaty with the Chippewa, 1820 (pp. 187–188), and then as Æneas Mackay, "captain U. S. Army," in the Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, 1832 (pp. 349–351). In addition, most Indian names were translated, so in the Treaty with the Comanche, etc., 1835 (pp. 435–438), participants such as Lachhardich, or the man who sees things done in the wrong way (p. 436) and Taytsaaytah, or the ambitious adulterer (p. 437) are introduced.

Yet, beyond the presence of some unique identifiers, there are in attendance some very significant historical signatories, even if their names were spelled differently a century and a half ago. Two major Sioux chiefs — Spotted Tail and Sitting Bull — were involved only in the Treaty with the Sioux — Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee — and Arapaho, 1868 (pp. 998–1007). Spotted Tail is represented by the Brulé appellation Zin-tah-gah-lat-skah, while Sitting Bull's formal Oglala name appears as Tah-ton-kah-he-yo-ta-kah. [26]

One immediate dividend of sorting the single occurrence list from the TokenX output is a series of names that are related in spelling to these two. The only comparable name to Spotted Tail's Zin-tah-gah-lat-skah is Zin-tah-skah, or White Tail. However, besides Sitting Bull's Tah-ton-kah-he-yo-ta-kah, there are also instances and translations of Tah-tong-ish-nan-na (One Buffalo); Tah-ton-kah-ho-wash-tay (Buffalo with a Fine Voice); Tah-ton-kah-ta-miech (Poor Bull); Tah-ton-kah-wak-kanto (High Bull); Tah-ton-kah-wak-kon (Medicine Ball; see discussion below); Tah-tonka-skah (White Bull); and Tah-tonk-ka-hon-ke-schne (Slow Bull).

The ability here, however, of TokenX to enumerate all these names leads to the identification of the apparent spelling error for the translation of Tah-ton-kah-wak-kon into Medicine Ball in the Treaty with the Sioux — Lower Brulé Band, 1865 (pp. 885–887). This error originated in the document's Statutes at Large text (14 Stat. 699, 701) and was merely copied during the original Kappler collation. Further, examination of the microfilmed image of the original treaty (Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722–1869, 1966, reel 14, ratified treaty number 340) reveals that the written name on the treaty — placed there for, and as a way to denote the active participation of, Tah-ton-kah-wak-kon — certainly could have been taken for Medicine Ball by someone unfamiliar with Indian personal names, and so the transcription process, from the initial instrument to the Statutes at Large rendering, turned most probably on this clerical error.

Locating this inaccuracy also helps confirm, based solely on the clear outcomes Tah-tong-ish-nan-na (One Buffalo) and Tah-ton-kah-ho-wash-tay (Buffalo with a Fine Voice), that whenever the Sioux spoke of, or used, the term bull, they always meant a male North American bison, Bison bison (Steelquist, 1998).

Gathering issues

Hunting, fishing, and gathering were crucial activities for the tribes then, just as now. [27] These actions are scattered throughout these documents, with the terms hunting (N = 90), fishing (N = 18); and gathering (N = 13) used quite frequently. Ranching, an activity that virtually symbolizes the intersection of Manifest Destiny, the development of the West, and creating capital, never appears. Ranches and ranchos appear only twice and once, respectively, in Article 3 and 4 of the Treaty with the Western Shoshoni, 1863 (pp. 851–853), and in the Treaty with the Shoshoni-Goship, 1863 (pp. 859–860). Similarly, mining appears only ten times in six treaties. Farming (N = 99); farms (N = 47); and farm (N = 34) — as elements related to agriculture (N = 51), the preferred post-treaty activity for the tribes — are much more prevalent. [28]

treaty or treaties

As might be expected from these diplomatic materials, the terms treaty and treaties appear 3,340 and 1,043 times, respectively. The terms document and documents appear just once or three times, while instrument and instruments are much more numerous (N = 92 and 15), as in "the delegates who sign and seal this instrument" from the Treaty with the Kaskaskia, Peoria, etc., 1854 (pp. 636–640), or in the text of Article 3 of the Treaty with the Oto and Missouri, 1833 (pp. 400–401) that declares "The United States agree to continue for ten years from said 15th July, 1840, the annuity of five hundred dollars, granted for instruments for agricultural purposes."

friendship

This term appear 329 times in these treaties, but as a ratio to the total number of words — 0.513 times per thousand — this is fairly absent. The focus on the creation of a legal document, instead of merely a record, for the event might logically be the reason for this relative dearth: as noted below, friendship is evident far more frequently in the British records.

Indian and Indians; President and chiefs

The collective terms Indian and Indians are habitually found, numbering 1,932 and 3,553 times. President is at hand 1,438 times, following chiefs at 1,479. The singular, chief, emerges 850 times, which may be a clear indication of the multilateral discussions that usually occurred during these negotiations. Chieftess is present just once in all these American treaties, and is located in Article 3 of the Treaty with the Potawatomi, 1832 (pp. 372–375) that gives four sections of land to Miss-no-qui, a chieftess. She appears twice, in this treaty and in the later Treaty with the Potawatomi, 1836 (pp. 458–459). It is in the latter document that her charming English name, Female Fish, is revealed.

cession, cessions, session, and sessions versus retrocession

These American treaties were primarily used to transfer tribal lands to the emerging nation. The presence of 539 uses of cession and 55 of cessions, as opposed to just one example of retrocession (in the Treaty with the Stockbridge and Munsee, 1856 ; pp. 742–755), is a manifestation of the use of these devices to gather land for the federal government. Land and lands were observed 1,872 and 1,854 times.

The term session would be expected here, as a designator for portions of various Congresses. An appropriate example may be found in Article 13 of the Treaty with the Miami, 1838 (pp. 519–524) that reads: "…should this treaty not be ratified at the next session of the Congress…." The word is misused, though, in four treaties, where cession was the correct noun. These instances are "…the abovementioned and foregoing articles of agreement and session…" ( Treaty with the Creeks, 1827 ; pp. 284–286); "as evinced in the preceding session or relinquishment…" ( Treaty with the Sioux, 1836 ; pp. 481–482); "In consideration of the above session, the United States agree to pay to the said tribes…" ( Treaty with the Nisqualli, Puyallup, etc., 1854 ; pp. 661–664); and "…where the boundary of the session to the Seminoles defined in the preceding article…" ( Treaty with the Creeks, etc., 1856 ; pp. 756–763). All four errors occur in Kappler's 1904 texts, but only the second, Sioux one was apparently carried forward from the 1903 compilation. [29] None appears in the Statutes at Large, so these textual faults were progressively induced over time. There is no incorrect use of the term sessions.

instalments, instalment, and therefor

Absent the old spelling of the first two words (The Oxford English Dictionary (1989, vol. 7, pp. 1039–1040) and the strict, object-oriented legal form of the last one (The Oxford English Reference Dictionary, 1995, p. 1496), these three elements occur 43, 7, and 162 times, as in "The remaining forty thousand dollars to be paid in sixteen equal annual instalments" ( Treaty with the Rogue River, 1853 ; pp. 603–605); "the payment of the last instalment of the moneys payable to the Wyandotts" (Treaty with the Wyandot, 1855; pp. 677–681); and "the Seminole Nation agrees to pay therefor the price of fifty cents per acre, amounting to the sum of one hundred thousand dollars" ( Treaty with the Seminole, 1866 ; pp. 910–915). Therefore is present 190 times.

Tribal names

The spelling varieties of tribal names are quite clear here. Kappler's standardized Potawatomi (N = 31) is submerged by an array of names acquired in the field, not from the specifications of the Department of the Interior: Potawattimie (N = 18), Potawatomies (N = 9), Potawatamies (N = 9), Potawatomie (N = 7), Potawatomy (N = 6), Potawatimie (N = 5), Potawattamie (N = 3), Potawattimies (N = 2), and single occurrences of Potawatimies, Potawatomees, Potawattomie, Potawa-tamies, Potawattamis, and Potawattamies.

A Few Interesting Errors

Errors originating in the Statutes at Large

-

mocasins

The term mocasins, in this case for the participant Ah-too-pah-she-pe-sha, the black mocasins in the Treaty with the Belantse-eota or Minitaree Tribe, 1825 (pp. 239–241), is incorrect in the Statutes and so surfaced during the construction of Kappler's text ensemble.

-

cramberry

As noted earlier, cramberry appears in the Statutes at Large entry for the Treaty with the Wyandot, etc., 1817 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 145–155). Eck (1990, p. 1) stated that the American cranberry, Vaccinium macrocarpon, "is indigenous to the North American continent. It is closely related to the European cranberry (V. oxycoccos L.) and the lingonberry, or mountain cranberry (V. vitis-idaea L.), which can be found throughout Europe, Asia, and parts of North America." With special reference to this fruit in the treaty with the Wyandot, it is useful to note that the American cranberry "is found growing naturally in the peat bogs of Virginia, and westward to Minnesota, also northward, and abundantly in the British Possessions. In Minnesota and Wisconsin it grows extensively, being gathered in large quantities by the Indians" (White, 1896, p. 8). Gillespie (1999) has a more recent assessment.

The appearance of the cranberry's bud led to its name, because "[j]ust before expanding into the perfect flower, the stem, calyx and petals resemble the neck, head and bill of a crane — hence the name, "craneberry," or "cranberry" (White, 1896, p. 7), but the term cramberry does exist in the literature. In one useful instance, Joseph Scott (1805, p. 367; emphasis added), in his geographical dictionary, described Grand Island near Buffalo, New York as "well wooded with oak, hickory, and beech… In the middle is an extensive cramberry swamp." The First American Cookbook (Simmons, 1984) is a facsimile of the 1796 publication American Cookery. The "Tarts" section contains a recipe for ones filled with cramberries (p. 30).

Errors originating in the 1904 version of Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties

Besides the misnamed Medicine Ball example from the Treaty with the Sioux — Lower Brulé Band, 1865 (pp. 885–887), there are other faults.

-

Samuel Miiler

Samuel Miller was a Muscogee signatory of the Treaty with the Kiowa, etc., 1837 (pp. 489–491) and is listed as such in the Statutes at Large at 7 Stat. 533, 535. Kappler, though, had him as Samuel Miiler and this error was carried into the OSU version. Miller was involved, with a correctly spelled name each time, in the earlier Treaty with the Creeks, 1825 (pp. 214–217), and the later Treaty with the Creeks and Seminoles, 1845 (pp. 550–552).

-

Iindians

This is an error in the original 1904 Kappler text, but not in the Statutes at Large, for Article 11 of the Treaty with the Makah, 1855 (pp. 682–685) that was designed to "…furnish them with the necessary tools and employ a blacksmith, carpenter and farmer for the like term to instruct the Iindians in their respective occupations." The error is also absent from the 1903 Kappler volume, so this inaccuracy arose during the preparation of the second edition.

Errors originating in the OSU conversion of Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties

-

Indiansn, Indianstook, reliquish, relinguish

These problems are, sequentially, a) part of the assent section of the Chippewa living near Sault Ste. Marie for Senate amendments to the Treaty with the Ottawa and Chippewa, 1855 (pp. 725–731); b) within the second paragraph of the Treaty with the Stockbridge and Munsee, 1856 (pp. 742–755), where it should read Indians took; and c) as single examples of the term reliquish and of relinguish that emerge in the preamble of the Treaty with the Appalachicola Band, 1833 (pp. 398–399), and in Article 1 of the Treaty with the Iowa, 1854 (pp. 628–631) among 178 relinquish, 81 relinquishment, 61 relinquished, 13 relinquishments, 7 relinquishing, and 6 relinquishes occurrences.

The British Treaties (N = 7)

Until recently, most of these seven documents were fairly scattered among only compilations of state histories. The digitization project carried out by UNL of these seven, as well as of the two absent American State Papers documents, was designed to complete the recognized treaty series started by OSU and to provide World Wide Web access to all 375 treaty items.

The corpus of these materials

There are 5,566 unique terms in these British documents, totaling 78,348 words. Within this array of 2,495 elements, or 45% are single element occurrences. Alphabetically sorted and word frequency files summarize these findings.

Some Interesting Exemplars

The five British treaty words with the highest frequencies

The words the, to, of, and, and you range in frequency from 5,239 to 1,467 times. There is no real difference for the rates across the first four of these words, when compared to those of the five words with the highest frequency in the American documents; only the order of the second through fourth elements has been shuffled. The interesting result here is the presence of 1,467 uses of the term you, but this is a very appropriate lexeme in materials that report on the verbatim discourse of negotiators. In all of the 368 American treaties, you is found just eight times.

Personal and place names

Distinctive personal names emerge from these materials. Besides that of Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Department at this time (Richter, 2004), there are unique names like Sagorrihwhioughstha, or Doer of Justice, that was created by the Indians for Governor William Franklin (1730-1813) of the province of New Jersey, the Loyalist son of Benjamin Franklin (Fennelly, 1949). This compliment was used to denote his deep concern for the protection of their rights. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary Line — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 was "Sealed and delivered and the consideration paid in the presence of" Franklin, as noted at the very end of this treaty (O'Callaghan, 1857, pp. 111–137), but his name is misspelled as Francklin twice within this document.

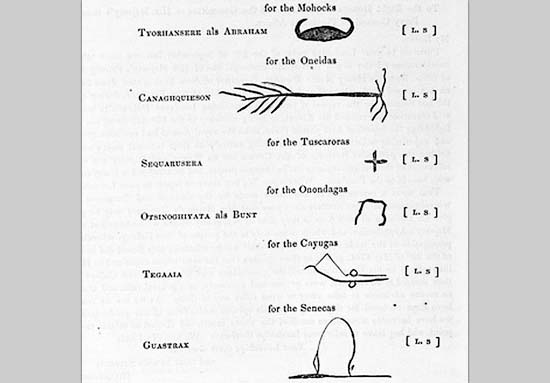

The transaction's signature section (Fig. 1) is decorated with the pictographs of Tyorhansere als (alias) Abraham for the Mohocks (or Mohawk); Canaghquieson for the Oneidas; Sequarusera for the Tuscarora; Otsinoghiyata als Bunt for the Onondagas; Tegaaia for the Cayugas; and Guastrax for the Senecas.

Fig. 1: Pictographs from the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary Line — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 .

The only real contract-like document in this British collection — the Deed in Trust from Three of the Five Nations of Indians to the King, 1726 (O'Callaghan, 1855a, pp. 800–801) — has a signature division with seven pictographs. These in turn are footnoted, to identify the six clans (Deer, Wolf, Bear, Turtle, Plover, and Beaver) of these sachem participants. [30] With its boundary descriptions pertinent to the task of the instrument, familiar place names mark off the geography: the River of Oniagara, a Creek Call'd Canahogue, and Lake Osweego, or today's Niagara and Cuyahoga Rivers, and Lake Oswego. It too has a "Signd Seald and Deliverd in the Presence of us" portion.

The term Grandfathers, with the initial capital, was used at the Conference Held By The Honourable Brigadier General Moncton with the Western Nations of Indians, at the Camp before Pittsburgh, 12th Day of August 1760 (Hazard, 1852, pp. 744–751) by the Chief of the Ottawa as a sign of respect when he remarked "We have heard what our Grandfathers, the Delawares, said Yesterday to you" during his comment to the British on the tribe's acceptance of the Covenant Chain of friendship.

In the evolving east-to-west geographic timeline of these negotiations with the tribes of America, place names like Connecticut (N = 21, and 1 Connecticutt, vs. 13 of the former in Kappler); Rhode Island (N = 20 vs. zero times in Kappler); and Massachusetts (N = 2 vs. 24 in Kappler), that are relatively rare or never appear in Kappler's treaty collation, salt these early British materials. Settlements like Tierondequat — near today's Irondequoit Bay at Rochester, New York, that in turn flows into Lake Ontario — dot these discussions. The French and their Huron allies had been through this area in the 1680s, in part to fulfill the demands of the Huron as a prerequisite for sustained fur trade with them (Heidenreich, 1978). Absent the economic effect, the main result of these incursions was the onset of endless bitter animosity between the French and the Iroquois Confederacy.

Gathering issues

Hunting activities appear in every single British treaty, while the terms fishing, gathering, and agriculture do not. There was infrequent discussion during British negotiations over these activities; the tribes were left to carry on, as they had since time immemorial. The same could not be said for the American transactions, where the acquisition of land through Indian cessions almost immediately precluded further use by tribal members.

treaty or treaties

The more social atmosphere of the negotiations between the tribes and the British did not preclude the use of the terms treaty or treaties. These emerge 87 and 31 times in these seven documents.

friendship, peace, brethren, Indians, and nations

The first term appears 77 times, found in all but ratified treaty number 2, the Deed in Trust from Three of the Five Nations of Indians to the King, 1726 (O'Callaghan, 1855a, pp. 800–801). The ratio of its frequency to the total number of all words in the British suite demonstrates that friendship has a rate of once per thousand, twice that found for the same term in the American treaties. At the same time, peace (N = 63) appears at a rate that is almost one and one-half times that reflected by the 435 occurrences of the word in Kappler' collation, while brethren (N = 269) mixes equally with Indians (N = 354) and with the collective nations (N = 351).

Majesty and sachem series

These terms are the British equivalents to the President and chief examples in the American suite. Elements of the Majesty series appear in each of the seven British treaties. Token-X identified Majesty or Majeſty (N = 27 and 1); Majesty's or Majeſty's (N = 16 and 2); Majestys (N = 14); Majty's (N = 14); Majties (N = 6); and Majty (N = 4) within these instruments.

The sachem array demonstrates the strong presence, in all but one of these transactions, of the organization of the Iroquois Confederacy. The examples include sachem (N = 2); sachems (N = 13); sachim (N = 11); and sachims (N = 39). Fenton (1998, p. 7; emphasis added) provided an image of the role of sachems: "Typically, Indian delegates who were appointed to represent the nation at treaty negotiations were front men for the sachem chiefs. Perforce these speakers and negotiators developed reputations as politicians who should be courted and heard. White people in the colonies who became knowledgeable about Indian affairs soon learned to distinguish two kinds of Indian leaders: war chiefs, who raised and led war parties and who in peacetime might be traders, and sachems, or peace chiefs, who confined their attention to civil affairs. What further complicated Indian affairs and confused colonials was that principals typically remained silent and appointed as their speakers artful men who were not of chiefly status. These speakers were often confused with the principals and labeled as sachems in the records. On occasion the principals, who were proper sachems, doubled as speakers, in which cases their names appear in the records."

cession

Any form of cession (N = 16) — as in "Boats loaded with the Goods intended for the Present to be made by the Cession of Lands to the King…" — appears only in ratified treaty number 7, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary Line — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 (O'Callaghan, 1857, pp. 111–137).

A Few Interesting Errors

-

English spelling of the time

There are numerous examples, such as perswade, that are out of place in today's spelling, but were perfectly acceptable when these British treaties were created. This term appears in The Great Treaty of 1722 Between the Five Nations, the Mahicans, and the Colonies of New York, Virginia, and Pennsylvania (O'Callaghan, 1855a, pp. 657–681) and in The Albany Congress, and Treaty of 1754 (O'Callaghan, 1855b, pp. 853–892). Persuade too appears in both of these perswade documents, as well as in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 (O'Callaghan, 1857, pp. 111–137). The Oxford English Dictionary (1989, vol. 11, pp. 610–611) has ample demonstrations of the use of both words during this period.

-

preist

The influence of the Catholic Church appears in these documents through this misspelling (there is only one priest as well). This error is found in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 (O'Callaghan, 1857, pp. 111–137) in a report that "A Deputation from the Aghquessaine Indians came to Sir Williams Quarters accompanied by the Oneida chiefs whose interposition with him had been requested in order to accommodate the unhappy difference which had gone such lengths in their village that their Preist and many of their people would likely be murthered" (emphasis added). Here, the "Aghquessaine Indians" are the Akwesasne Mohawk, from the Mohawk term ahkwesáhsne for "where the partridge drums." Akwesasne is the traditional missionary spelling that is related to the word ahkwesásne in the Oneida language (Fenton and Tooker, 1978, p. 479). "Their [Jesuit] Preist and many of their people" were under the risk of being murdered (see the murder entry in The Oxford English Dictionary, 1989, vol. 10, p. 108; murthered appears here as its only use within these seven items). Sir William was Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs. There are no church examples in this suite, and the only occurrence of the correctly spelled priest is in The Albany Congress, and Treaty of 1754 (O'Callaghan, 1855b, pp. 853–892).

Both collections (N = 375)

Average word count per document

One initial observation centers upon the two techniques employed by the American and the British governments to deliver the contents of these negotiations. The average number of words per document illustrates this point: the American treaties are 640,885 words encased in 368 documents, or just over 1,740 words per instrument. The British rate is six times higher — 78,348 words written into just seven contracts. If nothing else, these two widely disparate rates illuminate the processes of British kinship formation versus the American cession-contract approach in these two series of dialogues with the tribes.

Signature sections: his x mark, [L. S.], and [SEAL]

The 1904 edition of Kappler's volume two included sections for assents, various treaty adjustments, and rolls of signatories. These signature inventories allow an enumeration of the very persons who committed to these negotiations.

One clear manifestation of this is evident on the first signature page of the microfilmed copy of the significant removal Treaty with the Cherokee, 1835 (Ratified Indian Treaties, 1722–1869, 1966, reel 8, ratified treaty number 199). Eleven of the Cherokee signatures are indicated by marks: the first two entries on the left indicate "Cae-te-hee his x mark" and "Te-gah-e-ske his x mark." To the right of these are the signatures of General William Carroll and John F. Schermerhorn, acting as Commissioners for the United States at this transaction. In old British law, deeds required the seal, not the signature, of the signatory and this tradition continued, though with less strictness, in the United States. Here, the signatures or marks took the place of the seal, especially since these negotiations involved the tribes. The same signature list in Kappler's compilation uses the classic "L. S." or locus sigilli to indicate "the place of the seal" (pp. 439–449). Across Kappler's collection, there are signature registers that have [L. S.] or [SEAL] markers, and there are documents that do not. [31]

The presence of these indicators pervaded British, and other, negotiations. John Batman, who in 1835 purchased from the Aborigines of Australia the land upon which the city of Melbourne was erected, had each of eight chiefs make "his x mark" on the so-called Melbourne Deed, and confirmed these marks with a paired "L.S." The marks — and the actual seals — may be seen in Warner and Edge-Partington (1915, after p. 49). [32]

In Canada, Alexander Morris in Treaty 5 Between Her Majesty the Queen and the Saulteaux and Swampy Cree Tribes of Indians (Morris, 1880, pp. 342–350) used "[L. S.]" to validate his signature, but not those of the Indians involved, in his memoirs of the event. Some of the subsequent adhesions to this document contained a similar application of this indicator.

Within the African continent, "the British nurtured an enduring obsession with boundaries, promised land and exclusivity" in their dealings with the Maasai (Hughes, 2005, p. 222). Two Agreements — from 1904 and 1911 — were cited in full in the still disputed, so-called "Masai Case" before the Court of Appeal for Eastern Africa (Ol Le Njogo v. Attorney General, 1913). In the former transaction, Donald Stewart, His Majesty's Commissioner for the East Africa Protectorate declared that the document was "set [by] my hand and seal." The court's opinion displayed space in the text of the latter instrument for an "L.S." disk next to the statement "Signed, sealed and delivered" of Sir Edouard Percy Cranwill Girouard, "Knight Commander of the Most Distinguished Order of St. Michael and St. George, Member of the Distinguished Service Order, Governor and Commander-in-Chief of the East Africa Protectorate" (pp. 74 and 76, respectively). On a broader scale, Her Majesty the Queen, as "Suzeraine of the Transval State," ratified the 1875 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce, Boundary, &c., Between the South African Republic and the King of Portugal, with Protocol Annexed, Relating to the Lorenzo-Marquez Railway (Hertslet, 1967, pp. 246–249). The text of the Protocol for the railway was signed by the King of Portugal and by the President of the State of the South African Republic, each reinforced by an attendant "(L.S.)."

As one non-British example, the published text of the 1658 Treaty Between France and the Protestant Swiss Cantons (Parry, 1969, pp. 117–135) has huge spaces allocated to identify the sites of the original, equally large seals. [33]

here-, there-, and where- family

Tiersma (1999, pp. 93–95), through the use of these three models, remarked upon those words common to medieval English that were carried forward by later English legal vocabularies. Driedger (1949, p. 306) described the difficulty of interpreting hereinbefore and hereinafter while creating legislative text, by stating that the "[d]ifficulties of interpretation frequently arise through [the] use of referential words like aforesaid, herein, hereinbefore and hereinafter. If it is necessary to refer to something outside the section or subsection, a more specific reference should be made if possible." However, at the time of their negotiation, neither the contractual arrangement of the parameters of these Indian treaties, nor the need for clarity with non-English speaking cosigners, seemed to inhibit the use of these old legal terms. In the American treaties, each of the terms aforesaid (N = 917), herein (N = 484), hereinbefore (N = 92), hereinafter (N = 129) was prevalent. In addition, therein and whereas were present 109 and 407 times. [34] In comparison, the British documents held only 13 whereas; 4 wherein; 3 therein; and 2 herein occurrences, as perhaps yet another indirect display of the more social, rather than strictly legal, aspects of these negotiations. The Americans, particularly after the War of 1812, aggressively pursued tribal lands and so relied heavily upon contract law to attain these goals. The British, during their stay, relied more on the development of a relationship with the tribes that demanded far fewer land-transferring transactions.

The Oxford English Dictionary, though, very directly links the therein family of terms (therein, thereinafter, thereinbefore, and thereinunder) to text positions that are placed "after, before, below in that document, statute, etc." (1989, vol. 17, p. 210; emphasis added). The where- group commands a similar, albeit less legally oriented, explanation (1989, vol. 20, pp. 213–218). The disparity between the two lexicons used by these sovereigns, however, is the message here: different diplomatic conditions demanded the use of dissimilar, if still linguistically related, vocabulary.

Map coordinates, initials, and given name abbreviations

The "List of lands" in the Treaty with the Delawares, 1861 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 814–824) details township map coordinates for 100,000 acres of land in Kansas conveyed to the Leavenworth, Pawnee, and Western Railroad Company by the Delaware. Here, the array of range values cover 17 E through 23 E, accounting for many of the 470, single character e occurrences found in these treaties. The Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, 1867 (pp. 951–956) has section numbers too that include N, S, E, W, NE, SE, NW, and SW in the descriptions of lands finally allotted to tribal members that had been promised almost a decade before in the Treaty with the Sauk and Foxes, 1859 (pp. 796–799).

Initials within names are an additional source of lone character counts; there are 104 jr examples and dozens of Chas, Geo, Jas, Jno, and Wm truncations appear as well.

&, &c, &e, ¼, ½, £, †, and ‡

The ampersand (&) is found in both the American and the British suites (N = 45 and 893, respectively). The British use is especially noteworthy — this is the tenth most frequent term in that lexicon. The et cetera (&c) appears 74 and 43 times in these two collations, while the third item — the ampersand with an e — is a single error in the last line of the "Explanation" section in the Treaty with the Wyandot, 1832 (pp. 339-341) at the OSU web site; both the Statutes at Large and Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties have the normal et cetera, &c.

The quarter (¼; N = 55) and half (½; N = 64) fraction symbols are found in the allotment schedules attached to a number of treaties in Kappler's collection, as well as in township map coordinates. The three-quarter (¾) mark appears too, but only as a lone example in the total allotment value of 8,767¾ acres in the roll and schedule table of the Treaty with the Stockbridge and Munsee, 1839 (pp. 529–531).

The pound sign (£) is used twice, in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, or The Grant from the Six Nations to the King and Agreement of Boundary — Six Nations, Shawnee, Delaware, Mingoes of Ohio, 1768 (O'Callaghan, 1857b, pp. 111–137).

The dagger and double dagger — † and ‡ — are two marks used as cues to footnotes. [35] They are used once each in the Treaty with the Seneca, Mixed Seneca and Shawnee, Quapaw, etc., 1867 (Kappler, 1904b, pp. 960–969) to signal two, double township section number assignments for "Charles Martin" (#19 and 18), and for "Joel O. Loveridge, Geo. W. Loveridge, Alfred Loveridge, jointly" (#24 and 13), in the "Names of settlers, Nos. of land and price thereof, together with the amount deposited by each settler on the ten-section reserve, in Miami County, Kansas" portion of the document.

Future tasks with past words

The output derived from enumerating the various elements of the lexicons of these documents opens a number of worlds beyond that of diplomacy.

Of immediate interest are the two substantially different relative ratios for the term friendship. The British treaties used this word frequently, as part of the kinship-forming endeavors that the signatory tribes expected. The American documents were, in general, far less inclined to use this noun, let alone this behavior.

In addition, specialized materials are found in these instruments. For the geographer, there are over 40 river names, including more than a dozen occurrences of the Arkansaw, and five names of individual mountains or chains. For the zoologist, there are bear, beaver, bird, cat, cattle, deer, dog, fish, horse, moose, and swan. Absent the treaty question, there are doctor, mayor, soldier, and surveyor for the political scientists. The botanist may locate cypress, maple, oak, pine, and willow.

Much like the unknown world opened by the journals of the 1803–1806 expedition of Lewis and Clark, these treaties were intimate interactions. They not only provided a view into the personal lives of the aboriginal peoples of the New World, but a window as well into their own political, economic, and physical spheres. Benjamin Franklin's interest in the organization of the Iroquois Confederacy stimulated his suggestion — at the Continental Congress meeting in Albany in 1754 — that the new country consider creating a constitution based on that Confederacy's model. Johansen (1982, 1990, 1999) has established that there were far more American Indian influences at work than just those of the Haudenosaunee. The knowledge of the contributions of this larger tribal wealth only adds to the necessity to reexamine these treaty documents today.

In addition, the diversity of these lexical terms is an important demonstration of the power of TokenX. Its use with the texts of recognized Indian treaties allows the discovery of errors in the original Statutes at Large, of induced mistakes during the creation of the versions of Kappler's compilation, and/or of problems that were created during initial document scanning, optical character recognition (OCR) conversion of the texts, and/or final file editing. [36] The value of TokenX, however, is double edged. The creation of a lexicon imposes a new responsibility: all observed elements really should be examined. Potential visual errors, such as the word cramberry, always must be assessed along with true textual errors, shown here by the presence of Indiansn. The huge single occurrence list helped to detect easy errors in Kappler's 1,099 pages of volume 2, but the cession versus session revelations, for example, required special attention, thought, and knowledge of the language in use. Here, for whoever incorrectly transcribed those cession occurrences, the highly specialized nature of the treaty lexicon itself is responsible for these errors.

Yet, this is precisely why these documents are so attractive, and only the very tip of this fruitful iceberg has been touched by the few examples in this article. This enterprise can yield a myriad array of other new questions, a quantity that is matched only by the number of tribes and affected participants involved in these American and British transactions that forever changed North America. In the process of this study, the goal behind the development of TokenX was achieved — the materials in these two text suites were visualized and analyzed as never before. This success foreshadows the capability of others to use this tool to investigate virtually any digitized text that they may wish, including more deeply these treaties formed with the American Indians.

References

Adams, K. R. and Fish, S. K. (2006). Southwest plants. In W. C. Sturtevant and D. H. Ubelaker (Eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 3: Environment, Origins, and Population (pp. 292-312). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Agreement relating to civil air transport (with annex). Signed at Peking on 2 October 1975 [No. 17079]. (1978). United Nations Treaty Series 1106, 49–81.

American State Papers: Indian Affairs, vol. 1. (1832). Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton.

Anderson, J. H. (1898). Colonel William Crawford. Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly 6, 1–34.

Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1900. Indian Affairs. Report of the Commissioner and Appendixes. (1900). House of Representatives, 56th Congress, 2nd session. House Document No. 5, part 2–1 (Serial Set 4101). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Aquila, R. (1983). The Iroquois Restoration: Iroquois Diplomacy on the Colonial Frontier, 1701–1754. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Ashburn, E. (2007). A race to rescue native tongues. Chronicle of Higher Education 54 (5), B15.

Aust, A. (2000). Modern Treaty Law and Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bernholz, C. D. (2002). American Indian treaties and the Presidents: A guide to the treaties proclaimed by each administration. The Social Studies 93, 218–227.

Bernholz, C. D. (2003). Kappler Revisited: An Index and Bibliographic Guide to American Indian Treaties. Kenmore, NY: Epoch Books.

Bernholz, C. D. (2007). Adjusting American Indian treaties: A guide to supplemental article and supplementary treaty citations from opinions of the federal, state, and territorial court systems. Accepted for publication by Government Information Quarterly.

Bernholz, C. D. and Heidenreich, S. (2007). Locus sigilli and American Indian Treaties: Reflections on the creation of volume 2 of Kappler's Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Submitted to Government Information Quarterly.

Bernholz, C. D. and Holcombe, S. L. (2005). The Charles J. Kappler Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Internet site at the Oklahoma State University. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 29, 82–89.

Bernholz, C. D. and Weiner, R. J. (2007). Charles J. Kappler — A life beyond Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. In preparation.

Bernholz, C. D.; Pytlik Zillig, B. L.; Weakly, L. K.; and Bajaber, Z. A. (2006). The last few American Indian treaties — An extension of the Charles J. Kappler Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties Internet site at the Oklahoma State University. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 30, 47–54.

Billot, C. P. (1979). John Batman: The Story of John Batman and the Founding of Melbourne. Melbourne: Hyland House.

Bragdon, K. J. (2002). The interstices of literacy: Books and writings and their use in Native American southern New England. In W. L. Merrill and I. Goddard (Eds.). Anthropology, History, and American History: Essays in Honor of William Curtis Sturtevant (pp. 121–130). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Butler, E. (1881). Our Indian question. Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States 2, 183–221.

Butterfield, C. W. (1873). An Historical Account of the Expedition Against Sandusky Under Col. William Crawford in 1782. Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke & Co.

Calloway, C. G. (1990). The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600-1800: War, Migration, and the Survival of an Indian People. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Campbell, A. H. (1987). John Batman and the Aborigines. Malmsbury, Australia: Kibble Books.

Cannon v. Gorham, 136 Ga. 167 (1911).

Code of Federal Regulations: Title 25, Indians. (2007). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Cohen, F. S. (1947). Original Indian title. Minnesota Law Review 32, 28-59.

Conference and agreement between Plymouth Colony and Massasoit, Wampanoag sachem. (2003). In A. T. Vaughan and W. S. Robinson (Eds.). Early American Indian Documents: Treaties and Laws, 1607-1789, vol. 19: New England Treaties, Southeast, 1524–1761 (pp. 23–27). Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America.

Cutler, C. L. (1994). O Brave New World!: Native American Loanwords in Current English. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Deloria, V. and DeMallie, R. J. (1999). Documents of American Indian Diplomacy: Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775-1979. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Driedger, E. A. (1949). Legislative drafting. Canadian Bar Review 27, 291–317.

Driedger, E. A. (1963). Legislative Forms and Precedents. Ottawa: Queen's Printer.

Driver, H. E. (1969). Indians of North America (2nd ed., rev.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Driver, H. E. and Massey, W. C. (1957). Comparative studies of North American Indians. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (New series) 47(2), 165–456.

Du Ponceau, P. S. and Fisher, J. F. (1836). A memoir of the history of the celebrated treaty made by William Penn and the Indians under the elm tree at Shakamaxon, in the year 1682. Memoirs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania 3(2), 141–203.

Eck, P. (1990). The American Cranberry. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Ewers, J. C. (1975). Intertribal warfare as the precursor of Indian-white warfare on the northern Great Plains. Western Historical Quarterly 6, 387–410.

Feister, L. M. (1973). Linguistic communication between the Dutch and Indians in New Netherland, 1609–1664. Ethnohistory 20, 25–38.

Fennelly, C. (1949). William Franklin of New Jersey. William and Mary Quarterly (3rd series) 6, 361–382.

Fenton, W. N. (1998). The Great Law and the Longhouse: A Political History of the Iroquois Confederacy. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Fenton, W. N. and Tooker, E. (1978). Mohawk. In W. C. Sturtevant and B. G. Trigger (Eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast (pp. 466–480). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Ferris, R. G. (1967). Prospector, Cowhand, and Sodbuster: Historic Places Associated with the Mining, Ranching, and Farming Frontiers in the Trans-Mississippi West. Washington, DC: United States Department of the Interior.

Francis, W. N. and Kucera, H. (1967). Frequency Analysis of English Usage: Lexicon and Grammar. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Gibbon, J. (1881). Our Indian question. Journal of the Military Service Institution of the United States 2, 101–120.

Gillespie, A. K. (1999). Cranberries. In D. S. Wilson and A. K. Gillespie (Eds.). Rooted in America: Foodlore of Popular Fruits and Vegetables (pp. 60–88). Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press.

Goddard, I. (1996). Introduction. In W. C. Sturtevant and I. Goddard (Eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 17: Languages (pp. 1–16). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Goddard, I. and Bragdon, K. J. (1988). Native Writings in Massachusett, pt. 1. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society.

Gray, E. G. and Fiering, N. (2000). The Language Encounter in the Americas, 1492–1800. New York: Berghahn Books.

Guthrie, T. H. (2007). Good words: Chief Joseph and the production of Indian speech(es), texts, and subjects. Ethnohistory 54, 509–546.

Haycox, S. (2002). Alaska: An American Colony. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Hazard, S. (Ed.). (1852). Pennsylvania Archives (1st Series), vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Joseph Severns.

Heidenreich, C. E. (1978). Huron. In W. C. Sturtevant and B. G. Trigger (Eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15: Northeast (pp. 368–388). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution.

Hodge, F. W. (Ed.). (1906). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, pt. 2. House of Representatives. 59th Congress, 1st session. House Document No. 929 (Serial Set volume 5002). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Holcombe, S. L. (2000). Bringing Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties to the World Wide Web. Available at http://www.access.gpo.gov/su_docs/fdlp/pubs/proceedings/00pro11.html.

Howe, M. A. D. (1911). The Life and Labors of Bishop Hare: Apostle to the Sioux. New York: Sturgis & Walton Co.